Read excerpts from the interview below:

If you’d been walking past the Hearst Tower, in New York City, on the morning of September 6, I think you might have felt the building pulsating. About 200 people—Hearst magazine editors and execs, and some very pumped-up high school girls—were waiting, many literally on the edge of their seats, for my special guest to arrive. And all of these people had been sworn to secrecy—not just about what this special guest might say during our conversation, but about the fact that there even was a conversation, that my guest was even there. Absolute, total secrecy. From a room full of professional communicators and high school girls. Like I said: pulsating.

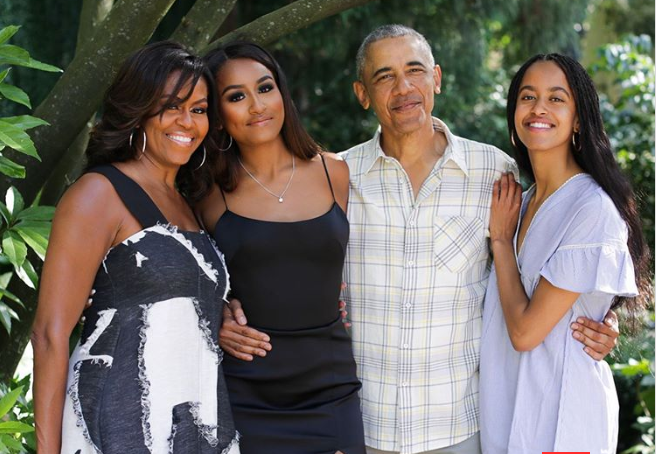

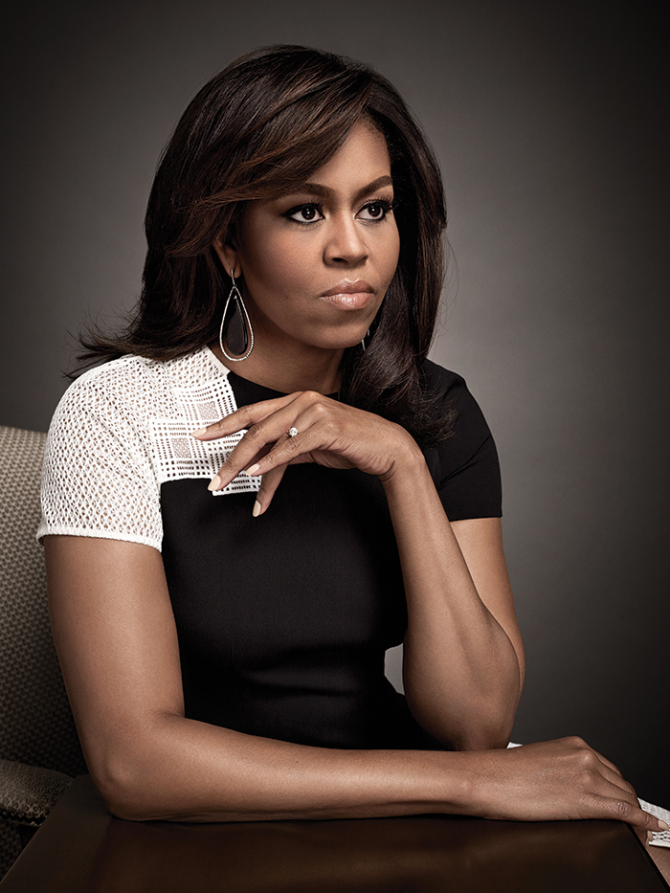

And who can blame them? Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama doesn’t do a lot of interviews, and this was her very first time talking about her new memoir, Becoming (Crown). It is a remarkable book—I urge, urge, urge you to read it. Because I have known Mrs. Obama for 14 years, and I can tell you: She is everything you think she is and then some. She served as our country’s first lady with such dignity, such grace, such style. Yet at the same time she really is just like all of us. I’m excited for you to see that about her, and to get to know her better, and to catch up on what she’s been doing the past two years. So prepare to be fascinated. And to everyone who was in that room back in September: You can exhale now!!!

Oprah Winfrey: First, let me just say: Nothing makes me happier than sitting down with a good read. So when I realized—in the preface!—what an extraordinary book was coming, I was so proud of you. You landed it. The book is tender, it is compelling, it is powerful, it is raw.

Michelle Obama: Thanks.

Why Becoming?

We actually had a blooper list of titles that we won’t go into here. But Becoming just summed it all up. A question that adults ask kids—I think it’s the worst question in the world—is “What do you want to be when you grow up?” As if growing up is finite. As if you become something and that is all there is. Do you plan to read Mrs. Obama’s memoir?

You grow up and you are many different things—as you have been many different things.

And I don’t know what the next step will be. I tell young people that all the time. You know, all young women probably have some magic number of what age you’ll be when you’ll feel like a grown-up. Generally, when you think your mother will stop telling you what to do.

[Laughs]

But the truth is, for me, each decade has offered something amazing that I would never have imagined. And if I had stopped looking, I would have missed out on so much. So I’m still becoming, and this is the story of my journey. Hopefully, it will spark conversations, especially among young people, about their journeys.

There are so many revelations in this book. Was writing about your private life scary?

Actually, no, because here’s the thing that I realized: People always ask me, “Why is it that you’re so authentic?” “How is it that people connect to you?” And I think it starts because I like me. I like my story and all the bumps and bruises. I think that’s what makes me uniquely me. So I’ve always been open with my staff, with young people, with my friends. And the other thing, Oprah: I know that whether we like it or not, Barack and I are role models.

image

Yup.

I hate when people who are in the public eye—and even seek the public eye—want to step back and say,“Well, I’m not a role model. I don’t want that responsibility.” Too late. You are. Young people are looking at you. And I don’t want young people to look at me here and think, Well, she never had it rough. She never had challenges, she never had fears.

We’re not going to think that after reading this book. We’re not going to think that at all.

[Laughs]

Millions of people have been wondering how you’re doing, how’s the transition—and I think there’s no better example than the toast story. Can you share the toast story?

Well, I start the preface right at one of the first weeks after we moved into our new home after the transition—our new home in Washington, a couple miles away from the White House. It’s a beautiful brick home, and it’s the first regular house, with a door and a doorbell, that I have had in about eight years.

Eight years.

And so the toast story is about one of the first nights I was alone there—the kids were out, Malia was on her gap year, I think Barack was traveling, and I was alone for the first time. As first lady, you’re not alone much. There are people in the house always, there are men standing guard. There is a house full of SWAT people, and you can’t open your windows or walk outside without causing a fuss.

You can’t open a window?

Can’t open a window. Sasha actually tried one day—Sasha and Malia both. But then we got the call: “Shut the window.”

-

» moreWalking Sunny and Bo at the 2014 White House Easter Egg Roll. (oprahmag)

[Laughs]

So here I am in my new home, just me and Bo and Sunny, and I do a simple thing. I go downstairs and open the cabinet in my own kitchen—which you don’t do in the White House because there’s always somebody there going, “Let me get that. What do you want? What do you need?”—and I made myself toast. Cheese toast. And then I took my toast and I walked out into my backyard. I sat on the stoop, and there were dogs barking in the distance, and I realized Bo and Sunny had really never heard neighbor dogs. They’re like, What’s that? And I’m like,“Yep, we’re in the real world now, fellas.”

[Laughs]

And it’s that quiet moment of me settling into this new life. Having time to think about what had just happened over the last eight years. Because what I came to realize is that there was absolutely no time to reflect in the White House. We moved at such a breakneck pace from the moment we walked in those doors until the moment we left. It was day in and day out because we, Barack and I, really felt like we had an obligation to get a lot done. We were busy. I would forget on Tuesday what had happened on Monday.

Mm-hmm.

I forgot whole countries I visited, literally whole countries. I had a debate with my chief of staff because I was saying, “You know, I’d love to visit Prague one day.” And Melissa was like, “You were there.” I was like, “No, I wasn’t. Wasn’t in Prague, never been to Prague.”

Because it’s happening at such a breakneck pace.

She had to show me a picture of me in Prague for the memory to jog. So the toast was the moment that I had time to start thinking about those eight years and my journey of becoming.

In reading the book, I can see how every single thing you’ve done in your life has prepared you for the moments and years ahead. I do believe this.

That’s if you think about it that way. If you view yourself as a serious person in the world, every decision that you make really does build to who you are going to become.

Yes, and I can see that from you in the first grade. You were an achiever with an A+++ attitude.

My mother said I was a little extra.

Getting those little gold stars meant something to you.

Yeah. Looking back, I realized there was something about me that understood context. My parents gave us the freedom to have thoughts and ideas very early on.

They basically let you and [your brother] Craig figure it out?

Oh gosh, yeah, they did. And what I realized was that achievement mattered, and that kids would get tracked early, and that if you didn’t demonstrate ability—particularly as a Black kid on the South Side from a working-class background—then people were already ready to put you in a box of underachievement. I didn’t want people to think I wasn’t a hardworking kid. I didn’t want them to think I was “one of those kids.” The “bad kids.” There are no bad kids; there are bad circumstances.

-

» moreBaby Michelle with her parents, Fraser and Marian Robinson, and brother, Craig. (oprahmag)

You mention this phrase that I like so much, I think it should be on a T-shirt or something. “Failure,” you say, “is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. It’s vulnerability that breeds with self-doubt and then is escalated, often deliberately, by fear.” Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. You knew this when?

Oh, first grade. I could see my neighborhood changing around me. We moved there in the 1970s. We lived with my great-aunt in a very little apartment over a home she owned. She was a teacher, and my great-uncle was a Pullman porter, so they were able to purchase a home in what was then a predominantly white community. Our apartment was so small that what was probably the living room was divided up into three “rooms.” Two were me and my brother’s; each fit a twin bed, and it was just wood paneling that separated us—there was no real wall, we could talk right between us. Like, “Craig?” “Yep?” “I’m up. You up?” We would throw a sock over the paneling as a game.

The picture you paint so beautifully in Becoming is that the four of you—you, Craig, and your parents—each was a corner of a square. Your family was the square.

Yes, absolutely. We lived a humble life, but it was a full life. We didn’t require much, you know? If you did well, you did well because you wanted to. A reward was maybe pizza night or some ice cream. But the neighborhood was predominantly white when we moved in, and by the time I went to high school, it was predominantly African American. And you started to feel the effects in the community and the school. This notion that kids don’t know when they’re not being invested in—I’m here to tell you that as a first grader, I felt it.

You say your parents invested in you. They didn’t own their own home. They didn’t vacation—

They invested everything in us. My mom didn’t go to the hairdresser. She didn’t buy herself new clothes. My father was a shift worker. I could see my parents sacrificing for us.

Did you know at the time it was sacrifice?

Our parents didn’t guilt-trip us, but I had eyes, you know? I saw my father going to work in that uniform every day.

-

» more6-year-old Michelle in 1970, with her dad’s Deuce and a Quarter. (oprahmag)

Your father drove a Buick Electra 225. So did my father.

Deuce and a Quarter.

Deuce and a Quarter.

We had our little aspirational moments when we’d get in the Deuce and a Quarter and drive to the nicer neighborhoods and look at the homes. But the Deuce and a Quarter for my father represented more than just a car because my father was disabled. He had MS, and he had trouble walking for quite some time. That car was his wings.

Yes.

There was power in that car. I call it a little capsule that we could be in and see the world in a way we normally couldn’t.

A window to the world. You know, I appreciate the way you were able to reveal not just what happened to your family, but what was going on with all families. We often talk about how systemic racism impacts generations. And the way you write about your grandfather Dandy—I thought this was so beautiful:

“Gradually, he downgraded his hopes, letting go of the idea of college, thinking he’d train to become an electrician instead, but this, too, was quickly thwarted. If you wanted to work as an electrician (or as a steelworker, a carpenter, or a plumber, for that matter) on any of the big job sites in Chicago, you needed a Union card. And if you were Black, the overwhelming odds were that you weren’t going to get one. This particular form of discrimination altered the destinies of generations of African Americans, including many of the men in my family, limiting their income, their opportunity, and eventually their aspirations.”

I don’t think I’ve ever heard a more gut-wrenching truth explained in such simple, human terms. Did your parents sit you and Craig down, at some point, and explain that the world isn’t always fair?

Oh, yeah, we would have conversations all the time. And my parents helped me to realize that there’s something that happens to a person who knows deep inside that they are more than what their opportunities allowed them to be. For Dandy, it bubbled up in him in a discontent that he couldn’t shake. That’s why my grandparents worked so hard to change our lives. And that’s one thing I understood. When I saw my grandparents and heard about their sacrifice, my notion was, Oh, little girl, you better get that gold star. They’re counting on you.

-

» moreMichelle Obama’s paternal grandfather, Fraser Robinson II (“Dandy”). (oprahmag)

It’s what Maya Angelou used to say: You’ve been paid for.

Absolutely.

So after high school, you went to Princeton and then Harvard Law School. And then you joined this prestigious law firm in Chicago. Now, this—when I read this, I put three circles around it and two stars. You write, “I hated being a lawyer.”

Oh God, yeah. Sorry, lawyers.

“I wanted a life, basically. I wanted to feel whole.” I wanted to shout that from the mountaintops because I know that so many people are going to read this who are in jobs that they hate but they feel like they have to continue. How did you come to that?

It took a lot to be able to say that out loud to myself. In the book, I take you on the journey of who that little striving star-getter became, which is what a lot of hard-driving kids become: a box checker. Get good grades: check. Apply to the best schools, get into Princeton: check. Get there, what’s your major? Uh, something that’s going to get me good grades so I can get into law school, I guess? Check. Get through law school: check. I wasn’t a swerver. I wasn’t somebody that was going to take risks. I narrowed myself to being this thing I thought I should be. It took loss—losses in my life that made me think, Have you ever stopped to think about who you wanted to be? And I realized I had not. I was sitting on the 47th floor of an office building, going over cases and writing memos.

What I loved about it is, it says to every person reading the book: You have the right to change your mind.

Oh gosh, yeah.

Were you afraid?

I was scared to death. You know, my mother didn’t comment on the choices that we made. She was live-and-let-live. So one day she’s driving me from the airport after I was doing document production in Washington, D.C., and I was like, “I can’t do this for the rest of my life. I can’t sit in a room and look at documents.” I won’t get into what that is, but it’s deadly. Deadly. Document production. So I shared with her in the car: I’m just not happy. I don’t feel my passion. And my mother—my uninvolved, live-and-let-live mother—said, “Make the money, worry about being happy later.” I was like [gulps], Oh. Okay. Because how indulgent that must have felt to my mother.

Yes.

When she said that, I thought, Wow—what—where did I come from, with all my luxury and wanting my passion? The luxury to even be able to decide—when she didn’t get to go back to work and start finding herself until after she got us into high school. So, yes. It was hard. And then I met this guy Barack Obama.

Barack Obama.

He was the opposite of a box checker. He was swerving all over the place.

-

» moreSharing ice cream in Iowa on the 2012 campaign trail. (oprahmag)

You write, about meeting him: “I’d constructed my existence carefully, tucking and folding every loose and disorderly bit of it, as if building some tight and airless piece of origami…. He was like a wind that threatened to unsettle everything.” At first you didn’t like being unsettled.

Oh God, no.

This I love so much—a moment that cracks me up: “I woke one night to find him staring at the ceiling, his profile lit by the glow of street lights outside. He looked vaguely troubled, as if he were pondering something deeply personal. Was it our relationship? The loss of his father? ‘Hey, what are you thinking about over there?’ I whispered. He turned to look at me, his smile a little sheepish. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘I was just thinking about income inequality.’”

That’s my honey.

[Laughs]

I mean, here’s this guy and—at the time, I was a young professional. This is when I was coming into my own, right? I had a job that paid more than my parents ever made in their lives. I was rolling with bourgeois class.

Uh-huh.

My friends owned condos, I had a Saab. I don’t know what’s cool these days, but a Saab, back in the day—oh yeah. I had a Saab, and the next step was, okay, you get married, you have a lovely home, and on and on and on. Yes, the bigger problems of the world were important. But the more important thing was where you were going in your career. I talk about Barack meeting some of my friends and how that didn’t really play out.

There was work we had to do as a couple. Counseling we had to do to work through this stuff.

[Laughs]

’Cause he’s this serious sort of income-inequality guy, and my friends are like…

You really let us into the relationship. I mean, down to the proposal and everything. You also write about some major differences between the two of you in the early years of your marriage. You say: “I understood it was nothing but good intentions that would lead him to say, ‘I’m on my way!’ or ‘Almost home!’ ”

Oh gosh, yes.

“And for a while, I believed those words. I’d give the girls their nightly bath but delay bedtime so that they could wait up to give their dad a hug.” And then you describe this scene where you’d waited up: He says, “I’m on my way, I’m on my way.” He doesn’t come. And then you turn out the lights—I could hear them click off, the way you wrote it.

Mm-hmm.

Those lights click, you went to bed. You were mad.

I was mad. When you get married and you have kids, your whole plan, once again, gets upended. Especially if you get married to somebody who has a career that swallows up everything, which is what politics is.

Yeah.

Barack Obama taught me how to swerve. But his swerving sort of—you know, I’m flailing in the wind. And now I’ve got two kids, and I’m trying to hold everything down while he’s traveling back and forth from Washington or Springfield. He had this wonderful optimism about time. [Laughs] He thought there was way more of it than there really was. And he would fill it up constantly. He’s a plate spinner—plates on sticks, and it’s not exciting unless one’s about to fall. So there was work we had to do as a couple. Counseling we had to do to work through this stuff.

Tell us about counseling.

Well, you go because you think the counselor is going to help you make your case against the other person. “Would you tell him about himself?!”

[Laughs]

And lo and behold, counseling wasn’t that at all. It was about me exploring my sense of happiness. What clicked in me was that I need support and I need some from him. But I needed to figure out how to build my life in a way that works for me.

The most important thing I think you said was that we live by the paradigms we know. And in Barack’s childhood, his father disappeared and his mother came and went. She was devoted to him, but was never really tethered to him. But you grew up in the square. The tight weave of your family.

His mother was in Indonesia, he was raised by his grandparents, he didn’t know his father—and yet even with this context, he was a solid guy. You realize that there are so many ways to live this life.

You also write, “When it came down to it, I felt vulnerable when he was away.” I thought that was kind of amazing, to hear a modern woman—a first lady—admit that.

I feel vulnerable all the time. And I had to learn how to express that to my husband, to tap into those parts of me that missed him—and the sadness that came from that—so that he could understand. He didn’t understand distance in the same way. You know, he grew up without his mother in his life for most of his years, and he knew his mother loved him dearly, right? I always thought love was up close. Love is the dinner table, love is consistency, it is presence. So I had to share my vulnerability and also learn to love differently. It was an important part of my journey of becoming. Understanding how to become us.

-

At the Iowa State Fair (oprahmag)

What was so valuable to me—and I think will be for everyone else who reads the book—is that nothing really changed. You just changed your perception of what was happening. And that made you happier.

Yeah. And a lot of the reason I share this is because I know that people look to me and Barack as the ideal relationship. I know there’s #RelationshipGoals out there. But whoa, people, slow down—marriage is hard!

You even say you all argue differently.

Oh God, yes. I am like a lit match. It’s like, poof! And he wants to rationalize everything. So he had to learn how to give me, like, a couple minutes—or an hour—before he should even come in the room when he’s made me mad. And he has to understand that he can’t convince me out of my anger. That he can’t logic me into some other feeling.

So what was the argument, or the conversation, that got you to say yes to him running for the presidency? Because you mention in the book that every time someone would ask him, he’d say, “Well, it’s a family decision.” Which was code for “If Michelle says I can, I can.”

Imagine having that burden. Could he, should he, would he. That happened when he wanted to run for state Senate. And then he wanted to run for Congress. Then he was running for the U.S. Senate. I knew that Barack was a decent man. Smart as all get-out. But politics was ugly and nasty, and I didn’t know that my husband’s temperament would mesh with that. And I didn’t want to see him in that environment.

But then on the flip side, you see the world and the challenges that the world is facing. The longer you live and read the paper, you know that the problems are big and complicated. And I thought, Well, what person do I know who has the gifts that this man has? The gifts of decency, first and foremost, of empathy second, of high intellectual ability. This man reads and remembers everything, you know? Is articulate. Had worked in the community. And really passionately feels like “This is my responsibility.” How do you say no to that? So I had to take off my wife hat and put on my citizen hat.

Did you feel pressure being the first Black family?

Uh, duh! [Laughs]

-

» moreWhite House Fourth of July celebration, 2015 (oprahmag)

Uh, duh. Because we’ve all been raised with You’ve gotta work twice as hard to get half as far. Before you came out, I was saying, “She’s meticulous, not a misstep—”

Do you think that was an accident?

I know it was no accident. But did you feel the pressure of that?

We felt the pressure from the minute we started to run. First of all, we had to convince our base that a Black man could win. It wasn’t even winning over Iowa. We first had to win over Black people. Because Black people like my grandparents—they never believed this could happen. They wanted it. They wanted it for us. But their lives had told them, “No. Never.” Hillary was the safer bet for them, because she was known.

Right.

Opening hearts up to the hope that America would put down its racism for a Black man—I think that hurt too much. It wasn’t until Barack won Iowa that people thought, Okay. Maybe so.

So my question is, when the weight of the world is on his shoulders, and you’re the shoulders that he’s leaning on, how did you carry that? How do you carry that?

Trying to be the calm in his swerve. Doing what I was taught: You know, when the leaves are blowing and the wind is rough, being a steady trunk in his life. Family dinners. That was one of the things I brought into the White House—that strict code of You gotta catch up with us, dude. This is when we’re having dinner. Yes, you’re president, but you can bring

your butt from the Oval Office and sit down and talk to your children.

Because children bring solace. They let you turn your sights off the issues of the day and focus on saving the tigers. That was one of Malia’s primary goals; she advocated throughout his presidency to make sure the tigers were saved. And hearing about what happened with what school friend—you know, falling into other people’s lives. Immersing yourself in the reality and the beauty of your children and your family. Plus, on the East Wing side, our motto was, we have to do everything excellently. If we do something—because the first lady doesn’t have to do anything—

[Laughs]

We were clear that what we were going to do was going to have impact and was going to be positive. The West Wing had enough going on; we wanted to be the happy side of the house. And we were. You’d have national security advisers coming over to brief me about something. They’d fall into my office—which was beautifully decorated, lots of flowers, and apples, and we were always laughing—and they’d sit down for a briefing and wouldn’t want to leave. “We’re done, gentlemen.” “We don’t wanna go back!”

There’s a section in the book that certain news channels are going to have a field day with. You write about Donald Trump stoking the false notion that your husband was not born in this country. You write, “Donald Trump, with his loud and reckless innuendos, was putting my family’s safety at risk. And for this, I’d never forgive him.” Why was it important for you to say that at this time?

Because I don’t think he knew what he was doing. For him it was a game. But the threats and security risks that you face as the commander in chief, not even within your own country but around the world, are real. And your children are at risk. In order for my children to have a normal life, even though they had security, they were in the world in a way that we weren’t. And to think that some crazed person might be ginned up to think my husband was a threat to the country’s security; and to know that my children, every day, had to go to a school that was guarded but not secure, that they had to go to soccer games and parties, and travel, and go to college; to think that this person would not take into account that this was not a game—that’s something that I want the country to understand. I want the country to take this in, in a way I didn’t say out loud, but I am saying now. It was reckless, and it put my family in danger, and it wasn’t true. And he knew it wasn’t true.

Yeah.

We had a bullet shot at the Yellow Oval Room during our tenure in the White House. A lunatic came and shot from Constitution Avenue. The bullet hit the upper-left corner of a window. I see it to this day: the window of the Truman Balcony, where my family would sit. That was really the only place we could get outdoor space. Fortunately, nobody was out there at the time. The shooter was caught. But it took months to replace that glass, because it’s bombproof glass. I had to look at that bullet hole, as a reminder of what we were living with every day.

You end the book by talking about what will last. And one of the things that has lasted with you, you say, is the sense of optimism: “I continue, too, to keep myself connected to a force that’s larger and more potent than any one election, or leader, or news story—and that’s optimism. For me, this is a form of faith, an antidote to fear.” Do you feel that same sense of optimism for our country? For who we are, as a nation, becoming?

Yes. We have to feel that optimism. For the kids. We’re setting the table for them, and we can’t hand them crap. We have to hand them hope. Progress isn’t made through fear. We’re experiencing that right now. Fear is the coward’s way of leadership. But kids are born into this world with a sense of hope and optimism. No matter where they’re from. Or how tough their stories are. They think they can be anything because we tell them that. So we have a responsibility to be optimistic. And to operate in the world in that way.

You feel optimistic for our country?

[Tears up] We have to be.

Ahh. Good job. Good job.

This story originally appeared in the December 2018 Issue of O.