Xia Peisu has been hailed “the mother of computer science in China.”

Throughout her long career, Peisu made numerous contributions to the advancement of high-speed computers in China and helped establish both the Chinese Journal of Computers and the Journal of Computer Science and Technology. A devoted educator, she taught China’s first course in computer theory and mentored numerous students. In 2010, the China Computer Federation honoured Peisu with its inaugural Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of her pioneering work in China’s computer industry.

In April 1960, China’s first home-grown electronic digital general purpose computer – the Model 107 – went live. Xia Peisu, the machine’s engineer and designer, had just made history.

After decades of war with Japan and the Chinese Civil War in the first half of the 20th Century, the country’s technological innovation had fallen behind much of the developed world. Chinese scientists relied heavily on hardware and expertise from the Soviet Union to build up their computing power after relying on the west.

But when the relationship between China and Soviet Union dissolved in 1959, China was once again isolated and it had to look inward for a way forward in an increasingly computerised world.

Within a year of the Soviet Union withdrawing aid, Xia delivered the 107 – China’s first step on the road to independence in computing.

Although currently,China happens to be a global leader in computer production. In 2011, they surpassed the US to become the world’s leading market for PCs, and the desktop PC segment of their computer industry alone is projected to bring in a revenue of over $6.4bn (£4.9bn) this year.

Xia was an important personnel to this. She helped shape some of China’s first computing and computer science institutions and developed their training materials. She taught the first computer theory class in the country. Over her career, she would usher hundreds of students into the country’s burgeoning field of computer science.

In the aftermath of war and political upheaval, Xia shaped a new field of science and a new industry in China. Through both her technological innovations and the many students she taught, Xia‘s influence resonates throughout China’s computing world today.

Born into a family of educators in the south-eastern municipality of Chongqing on 28 July 1923, Xia rarely went without an education. First attending primary school aged four and receiving private home tutelage at eight, she went on to excel at Nanyu Secondary School and graduated top of her high school class at National No. Nine in 1940.

Xia Peisu’s home of Chongqing, China during a Japanese airstrike in 1940 (Credit: Getty Images)

Xia graduated with a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1945. The same year she met Nanjing war refugee and fellow National Central alumnus Yang Liming, now a professor of physics at the university.

Xia developed methodologies that could more accurately predict variations in frequency and amplitude within electronic systems, which led to wide-reaching applications for any system with an electrical frequency, from radios to TV to computers.

In 1950, she was awarded her PhD. Later that same year, she married her husband in Edinburgh. Both scientifically-minded and deeply invested in putting those minds to work in their home country, the couple returned to China in 1951. They both took up positions at Tsinghua University (or Qinghua University), where Xia worked on telecommunications research.

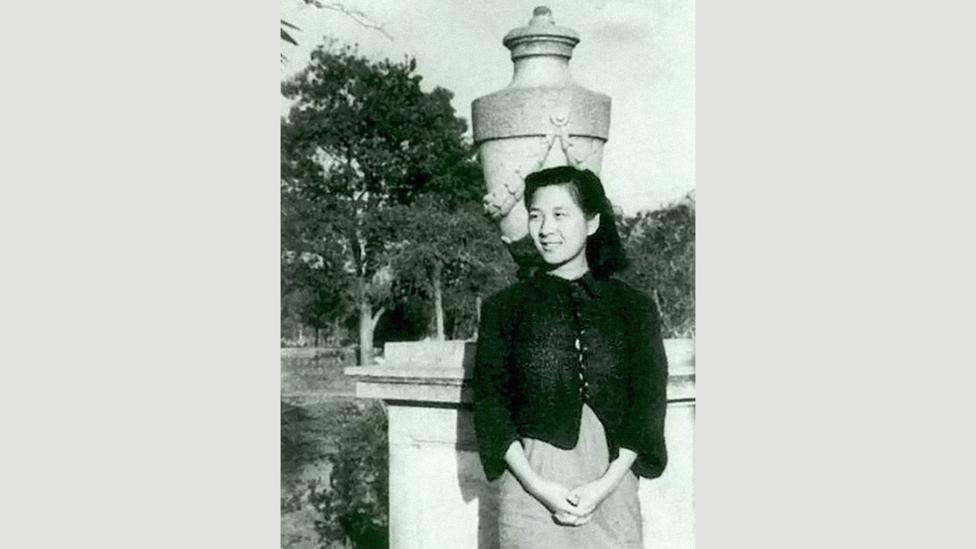

Xia Peisu would go on from a PhD in electrical engineering to designing China’s first home-grown electronic digital general purpose computer (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

In 1950, the USSR and China joined an alliance, a relationship that would directly impact China’s computing industry (Credit: Getty Images)

Xia became intricately tied to Sino-Soviet partnership when, in 1953, mathematician Hua Luogeng visited her place of work at Tsinghua University and recruited her into his computer research group at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). She was now one of the three founding members of China’s first computer research group.

With her knowledge of electronics and mathematics, Xia was an ideal choice

In 1956, she joined a delegation to Moscow and Leningrad to explore Soviet research, production and education in computing. When she returned that same year, she undertook translation of Soviet computer design from Russian into Chinese, including a 1,000-page manual that became the course text for teaching Chinese students Soviet computing.

Xia was involved in developing the computer science courses at both institutions, and as a course developer and lecturer, she oversaw the training of hundreds of students between 1956 and 1962.

“What [China] needed above all was a training program,” Mullaney notes. Xia gave them one.

By 1959, China had succeeded in replicating two Soviet electronic computer designs; the 103 model and the 104 model, each based on the Soviet M-3 and BESM-II computers respectively. But just as China began making progress in producing computers, the Sino-Soviet relationship was in dissolution.

The relationship had become so bad by 1960 that the Soviet Union withdrew all support, both material and advisorial, from China, says Mullaney. After the Soviets withdrew, many other countries assumed that China’s computing industry just stopped.

It didn’t.

Far from stopping after the 1960 USSR withdrawal of support, China’s computing industry continued to advance (Credit: Getty Images)

Xia’s 107 model was the first computer that China developed after Soviet withdrawal, and unlike the 103 and 104 models based on Soviet design, the 107 was the first indigenously designed and developed computer in China.

Throughout this time, Xia continued a balance of research and development in high processing speed computers and training new computer scientists and engineers. In 1978, Xia helped found the Chinese Journal of Computers as well as the Journal of Computer Science and Technology, the first English-language journal for computing in the country. And in 1981, she developed a high-speed processor array called the 150AP. Compared to the earlier Soviet-based model 104 that performed 10,000 operations per second, her 150AP boosted a computer’s operations to 20 million per second.

Due in large part to Xia, computer science coalesced into an independent field of study in China and the country’s computer industry emerged despite a tumultuous beginning. “In terms of someone who held her position and was such a central actor in a leadership role, I have not come across other women of her stature at that time,” Mullaney says.

By the 1970s, China had developed powerful, sophisticated computers with integrated circuits (Credit: Getty Images)

She was later named the processing chip of China’s first CPU computer “Xia 50”.

Dubbed in China the “Mother of Chinese Computing”, Xia is still recognised as a founding member of the country’s computer industry. The China Computer Federation awards the Xia-Peisu Award annually to women scientist and engineers “who have made outstanding contributions and achievements in the computing science, engineering, education and industry”. Chen Zuoning and Huan Lingyi received the award most recently in 2019: Chen for her work in developing domestic high-performance computing systems and Huan for her research in CPUs and other core computer devices. Continuing along the path Xia charted for them, Chen and Huan have strengthened China’s domestic computer technology.

In a world of lost untold stories of heroes, BBC new Future column, “missed geniuses” is out to celebrate them today.

For full article click here

Comments are closed.